The human body is a marvel of biological engineering, each part serving a purpose and contributing to our overall functionality. Understanding the external anatomy is not just for medical professionals or artists—it’s also essential for educators, students, and the curious minds eager to learn how we’re structured from the outside. This guide is crafted to provide a comprehensive look at labeling external body parts with clarity and intrigue.

TL;DR: This article delves into the fascinating world of external anatomy, guiding you through key anatomical landmarks from head to toe. You’ll learn how to identify and label each external feature accurately. Whether you’re studying for an exam, enhancing your art skills, or simply curious about the human body, this guide is for you. Visual cues and image placement suggestions are included to aid in understanding.

The Importance of Understanding External Anatomy

External anatomy, or surface anatomy, refers to the study of external bodily features and how they correlate with the underlying organs and systems. It’s critical in various fields:

- Medical professionals rely on surface anatomy to place stethoscopes, draw blood, or palpate organs.

- Artists and illustrators use it for accurate body proportion and dynamics in their work.

- Teachers and students benefit from fundamental knowledge of human structure for biology and health studies.

Recognizing these parts and understanding how to name and locate them precisely can also enhance your communication skills during health-related conversations.

Head and Face Anatomy

The head and face are rich in distinct features, each with their own labels. Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Scalp – The skin covering the skull, extending from the forehead to the nape of the neck.

- Forehead – Located just above the eyebrows, under the hairline.

- Eyes – Lined by the eyelids on top and bottom; includes pupils, irises, and sclera.

- Nose – Central protruding feature used for smell and breathing; includes nostrils and nasal bridge.

- Mouth – Bordered by the upper and lower lips; contains teeth and tongue internally.

- Ears – Located bilaterally, used for hearing and balance; includes lobes, auricle, and canal opening.

- Chin – The lowermost part of the face, under the lower lip.

Labeling practice often starts with these areas because of their prominent visibility and functional importance. Examining symmetry can also aid in identifying abnormalities.

Neck and Shoulders

The neck supports the head and connects it to the torso. It’s home to important blood vessels and the trachea. Key landmarks to note:

- Neck – Defined by the anterior (front), posterior (back), and lateral (sides).

- Adam’s apple – More visible in males, it’s part of the larynx and usually seen in the anterior neck.

- Clavicle – The collarbone, forming the upper boundary of the thorax.

- Trapezius – A major back muscle extending from neck to mid-back, forming the contour of the upper shoulders.

- Deltoid – The muscle capping the shoulder, important in adjacent arm movement.

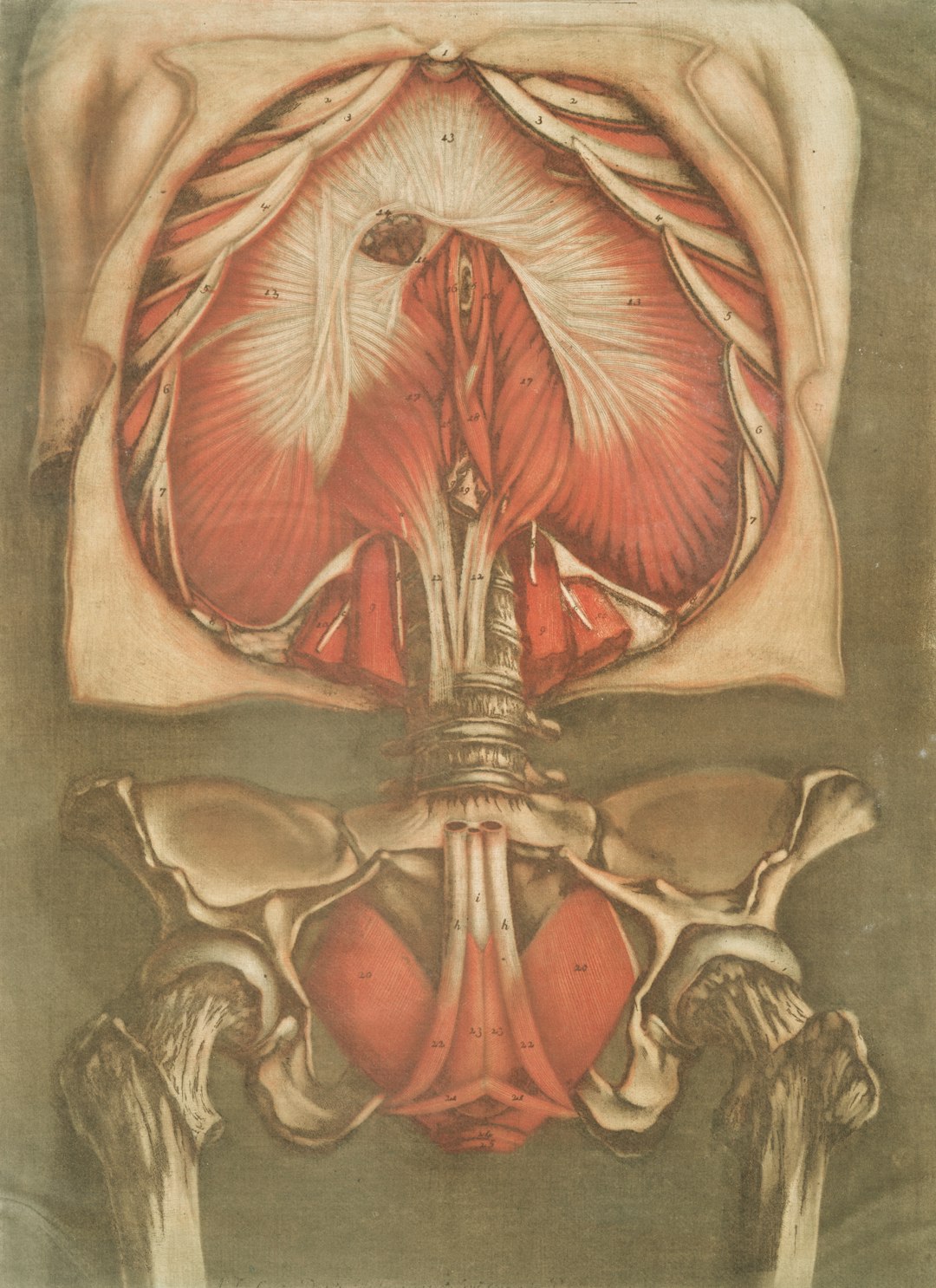

Torso and Chest

The torso includes the chest (thorax), abdomen, and back areas. All these regions are pivotal in body movement and protection of internal organs.

- Chest/Pectoral region – Houses the ribcage and sternum; in males and females, includes nipples.

- Navel (umbilicus) – The belly button, centrally located in the abdomen.

- Axilla (armpit) – The area beneath the junction of the upper limb and torso.

- Scapula – Shoulder blades located on the upper back, aiding in arm movements.

Learning this region is vital for understanding posture, breathing mechanics, and even emergency first aid like CPR, where chest landmarks are key.

Arms and Hands

When labeling the upper limbs, precision matters because of the limb’s complexity and high mobility. Important areas include:

- Humerus – The upper arm bone extending from the shoulder to the elbow.

- Elbow – The hinge joint connecting the upper and lower arms.

- Forearm – Extends from the elbow to the wrist, made of the radius and ulna bones.

- Wrist – Connects the hand to the forearm with multiple small bones.

- Hand – Include finger digits, knuckles, palm, and the dorsum (back) of the hand.

Knowing arm terminology is essential for sports physiotherapy, ergonomic evaluations, and everyday communication about injuries or motion restrictions.

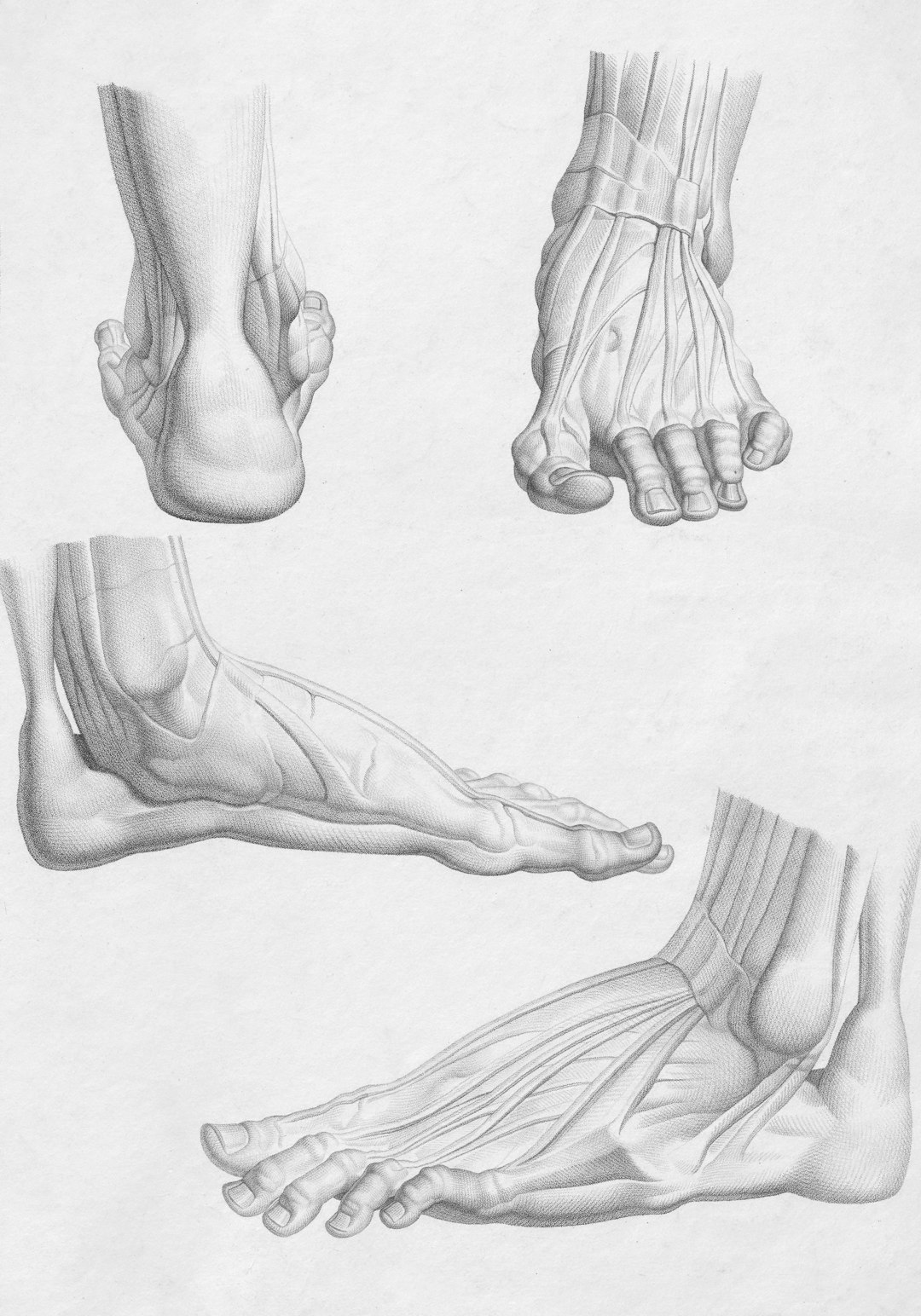

Legs and Feet

The lower limbs are designed for strength and mobility. Key anatomical terms include:

- Hip – The joint where the thigh connects to the pelvis.

- Thigh – Includes the femur, the strongest bone in the body.

- Knee – Includes the kneecap (patella) and serves as a major hinge for leg movement.

- Calf – The posterior lower part of the leg, housing the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles.

- Shin – The front part of the lower leg, protected by the tibia bone.

- Foot – Composed of the toes (phalanges), arch, and heel.

External features of the legs are important for diagnosing conditions like swelling, injury impact zones, and variations in walking gait.

Labeling Systems and Mnemonics

To facilitate memorization, experts use educational tools like anatomical models, flashcards, and apps with 3D body scans. Here are a few popular mnemonics:

- “Some Lovers Try Positions That They Can’t Handle” – For wrist bones (Scaphoid, Lunate, Triquetrum…)

- “On Old Olympus Towering Top, A Finn And German Viewed Some Hops” – For cranial nerves.

Creating your own mnemonic based on the body part group you’re studying can make retention even more effective. Color-coded diagrams are also highly beneficial.

Tips for Labeling External Body Parts

- Start top-down: Scan the body from head to toe to maintain systematic labeling.

- Use symmetry: Comparing left and right sides improves observation skills.

- Involve touch: Palpating the area while learning can reinforce spatial awareness.

- Consult reliable charts: Invest in high-quality anatomy posters or use verified anatomy apps.

Conclusion

An understanding of external anatomy opens the door to greater observation, improved health communication, and deeper insights into how our bodies function in everyday life. Whether you’re an aspiring doctor, artist, or lifelong learner, mastering these labels equips you with an essential toolkit. Consider supplementing your studies with interactive diagrams and real-world practice for the most engaging learning experience.

Now that you’ve gone through the comprehensive overview, take a moment to explore your own anatomy—stand in front of a mirror and begin identifying each region. The body’s story is written on its surface; all you have to do is learn to read it.